Emily Hall Tremaine (1906-88) was attracted to art in which theory and technology served as conduits for intuition. “You see a prophetic vision, especially if you train yourself to see it,” she explained. “You almost see what’s coming through the artist.” In her stellar art collection that eventually surpassed 400 works, one of the best examples was Paul Klee’s Departure of the Ghost, which Tremaine purchased in February 1945, three months before the end of World War II in Europe.

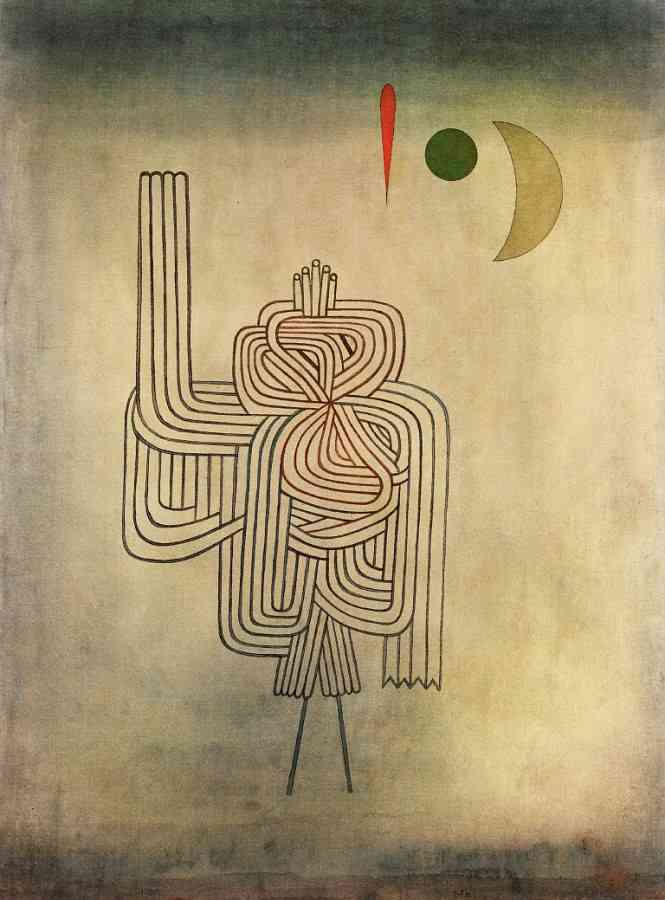

Paul Klee, “Departure of the Ghost”, watercolor

To Klee, theory “is fine but it has its limits; intuition remains indispensable.” So also technology is fine but only as a means to achieve liminal forms. In his art, machines can be organic while birds can be mechanized, even their song reduced to wires and springs. So also his ghosts thrum with life while communicating in code.

Klee painted Departure of the Ghost in 1931, the year that he left the Bauhaus where he taught painting, stained glass, and metalworking. At that time, he and his colleagues were bullied, being labeled as degenerates by the Nazis. Departure of the Ghost is not about silence but about being forcibly silenced—and yet finding a way to speak on multiple levels.

Earlier in his life when his style had begun to evolve, Klee had described his new direction as “abstract, with memories.” Indeed, the ghost has memories—a personal history filled with longing and loss. One would expect the ghost to be fearful; instead, it is plaintive, like a child waving good-bye to friends and family from the deck of a ship never to see them again. This is a painting that lingers in the mind. It haunts.

Departure of the Ghost is like a palimpsest, which is a medieval manuscript in which the original text has been erased so that the vellum can be reused, yet the erasure is not total, allowing pale glimpses of the original text beneath the new text. For an artist who was a master colorist, Klee used little color in the painting. There is a whiff of red in the circulatory lines that appear where the heart should be. The background is a faded blue. Similarly, the ghost verges on transparency but remains corporal by means of labyrinthine lines. There are also indecipherable symbols that are like echoes of a lost language.

The danger for the collector of such works of art was to over-focus on structure that, like technology, helped carry the message but was not the message.

While the comparison of Departure of the Ghost to a palimpsest is apt, Klee himself would have used the musical term polyphony to describe the deep reverberation of time and space in his art. To Klee, a talented violinist, polyphony meant the simultaneous presentation of emotional, intellectual, and sensory information.

Tremaine purchased Departure of the Ghost from Karl Nierendorf, an art dealer who had come to New York from Germany in 1936. He had brought with him a collection of Klee’s paintings that he prized. In fact, it had been Klee who had encouraged Nierendorf to become an art dealer in the first place. Until Nierendorf’s death in 1947, he continued to champion Klee, who had died in 1940, but he had little success in selling his paintings.

At the time of the purchase, Tremaine herself was coming out of a bleak period in her life in which she had been married to an abusive Nazi-sympathizer. She had left behind her play-girl lifestyle in California, and was charting a new course for herself in New York that included art collecting and, in May 1945, marriage to Burton Tremaine, an industrialist.

There is more than one version of Departure of the Ghost. The version Tremaine purchased is oil on muslin (43” x 30”). She hung it in her apartment near Piet Mondrian’s monumental Victory Boogie-Woogie. Both paintings stayed in the collection until near the end of her life. Tremaine said that the paintings she preferred were quiet and architectonic, meaning they possessed a subtle underlying structure that enabled artists to achieve something higher. The danger for the collector of such works of art was to over-focus on structure that, like technology, helped carry the message but was not the message. Aware of that danger, Tremaine challenged herself to see what was “coming through” the artist. “After half a century, collecting, for us, increasingly becomes a quest for the sublime,” Tremaine explained.

Leave a Reply